Painting at a time when painting is dead.

I have been working with Curator Lisa Dorin to develop text for our website about the painter Monika Baer. During my current Fellowship I have been professionalizing my writing practice, while still keeping accessibility at the forefront of my thinking. I would love any feedback on whether or not this text is accessible for those unfamiliar with Baer’s work or contemporary painting.

Baer’s work investigates whether it is possible to develop a new language around painting. She is not afraid to explore the abject, the lowbrow and the spectacle and performance of viewing works in a gallery. My piece on L is below:

Monika Baer’s paintings blend juxtaposing styles to develop a new form of painting despite its historic association with master artists. Baer studied painting at the Dusseldorf Art Academy from 1985-1992, a time when the Conceptualism of the 70s had exhausted meta explorations of painting. Baer’s contemporaries were interested in investigating forms of photography. Little mentoring existed for Baer as an emerging painter. In spite of these constraints, Monika Baer chose to dedicate her art practice to painting and pushes conventions by mixing techniques in a single composition.

Baer uses a method of painting developed from her own language of repeated symbols, kitsch and theatrics. She creates each work as a part of a series, rather than a single painting. Baer repeats shapes and forms from previous paintings as if they were characters making repeat appearances throughout her oeuvre. Baer’s first recognized works featured a series of marionettes performing on the canvas as a stage- a motif Baer returns to in all of her work. Her canvas is a loosely defined stage, the objects placed onto her ethereal backdrops hint at a narrative, which is more elusive than direct.

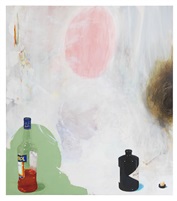

In her painting, L, two meticulously rendered liquor bottles stand in the foreground against an ethereal pastel backdrop. An imagined ledge holds the bottles in place for the viewer. Though beautifully rendered, the opened liquor bottle suggests something dark and sinister. The cap sits below a muddy brown splotch scraped into the canvas. Looking closely, smeared paint, a bulbous-nosed man, a bone and a figure emerge from the backdrop behind the bottles.

The mixture of beauty and abject, rendered realism and ethereal expressionism, highlight the contrasts Monika Baer explores throughout her artwork. Her practice draws interest back into the world of painting, at a time when many in the art world felt the medium was so overwrought with meaning and references it would be impossible to say anything new.

the necessity of the utopia (thinking about and reading Open Field: Conversations on the Commons)

While living in Providence I spent a lot of time meeting artists and teens involved in making at New Urban Arts. The studio was much more than an afterschool program, and much more than a maker-space. It was an open utopia with free admission for anyone seeking a space to explore ideas, or just to spend time with other people.

NUA’s goals included fostering the creative community and conversations around creative practice. At one of these conversations artist Ian Cozzens remarked that, “just because leaving the utopia is hard, does not mean the utopia should not exist.”

Art is not only aesthetics. Art can be a window into reimagining our shared experience. Social Practice artists indulge in exploring the possibilities of altered reality; they experiment by convening social situations existing under new rules that re-examine popular assumptions.

With a passion for museums, social practice art and community projects (and utopias), I have long been curious about the Walker’s experiment with Open Field. I’ve been exploring Sarah Shultz’s reflections and interviews in her book, Open Field: Conversations on the Commons. Since 2010 the Walker Art Center adopted the commons as a philosophical and programmatic framework for their open field in the summertime. Open Field is a public communal gathering space open to all community groups, artists, musicians for programs. Read more about it here.

Open field has been both criticized and applauded for being utopian. For her book, Sarah Schultz interviewed Stephen Duncombe about this criticism. His response resonates with my thinking this afternoon:

We need utopian thinking because without it, we are constrained by the tyranny of the possible. Look where realistic thinking has gotten us: a looming ecological crises that may exterminate life on the planet; and a state of normality whereby the rich get richer and more powerful, while everyone else gets poorer and more powerless. This is reality, and to imagine something other than this takes a bold leap.

Meanwhile, critics of the status quo act as if criticism is enough, an appropriate response to the unfolding apocalypse that is now. They seem to believe that criticism itself will transform society. It’s not that easy. Criticism is part of the very system itself. By its condition, criticism always remains obedient to the present: the object it criticizes. That is, criticism is wed parasitically to the very thing it ostensibly wants to change. There is no transformative moment. Besides, liberal democracies such as ours need critics in order to legitimate themselves as liberal democracies; it’s part of the system.

The political problem of today is not a lack of rigorous analysis, or a necessity for the revelation of the “truth,” but instead the need for a radical imagination: a way to imagine a world different from the world we have today.

Engaging the Young Professional

Today’s #edutues twitter chat investigates how museums engage young professionals in the museum world. It’s been a fun and interesting chat, but sometimes 144 characters is not enough to delve into the complexities and nuances of talking about this audience. I’m extrapolating some of my ideas here.

In order to successfully engage a young professional/young adult audience a museum must be comfortable with taking risks, trying new things and partnering with local creatives. Here are a few lessons I have learned from observing success-stories in the field:

–Show Trust–

A younger audience may be at odds with a museum formality and classic visitor expectations. Millenials are at an exploratory age (just out of college, exploring the career world) and coming up against the challenges that come with exploration. This audience is developing their professional voice and inventing new career paths in the digital era.They are easily criticized for an overindulgence in social media, short attention spans, criticized for their informality.

Museums can feel intimidating. Museums need to show trust to this audience.

The Williams College Museum of Art currently explores this idea through lending out original works of art to college students via the WALLS program. Students line up and pick out works on a first-come-first-serve basis to hang in their dorm/living spaces. That’s right. The museum loans out works from the collection for dorm rooms. It has become a popular way for students to build a personal connection to an artwork, and a personal connection to the museum. The entire program runs on trusting the students to care for the work.

– Build Creative Partners–

The Denver Art Museum released a report after a three year engagement experiment geared towards young audiences. They concluded that the programming they worked with engaged more of a style, rather than an age range.

“We originally thought of this audience as an age group but later realized that style, not age, was a better way to categorize the target audience.”

The biggest cause for their success? Building authentic partnerships with creative partners outside of the museum. Lindsey Housel, the Adult Programs Coordinator at the time, uses the metaphor of the museum as a front porch that I constantly return to in my work:

In the course of working on her master’s thesis, DAM educator Lindsey Housel researched public and private spaces and came up with the idea of the front porch as a meeting place that’s neither wholly private or public. “It’s like having a party at your house,” she explains. “It’s your space, but you don’t entirely control what happens. It’s also about the people who are coming and what they bring to the table. You can’t always be sure of the outcome, but as long as you are being true to who you are, that’s okay.” That part about being “true to yourself” is important. It can’t be a forced effort; it has to resonate with an institution’s overall values and mission while at the same time welcoming other perspectives and remaining open to collaboration and co-creating.

–Keep your content Authentic–

I’ll return again to the Denver Art Museum’s report: although irreverence is good, irrelevance is not.

Informality is not always shallow. Delivering substantive content in a personable context seems to hit a sweet spot for this audience. Museums should not shy away from delving into their rich content. Programming should focus on creating authentic connections with the substantive ideas museums explore themselves through exhibitions- otherwise the museum becomes a venue rather than a host.

Selfie-Help

The Selfie.

Mock it, love it, hate it: the museum selfie is here. With the invention of the Selfie Stick, museums in NYC are adopting a ban. Though we haven’t seen any selfie-sticks around WCMA, we do have a problem with selfies having close encounters with the art. Particularly with this piece:

George Segal, Couple in Open Doorway, 1977

This piece sits on the landing of the stairwell leading up into our galleries. Though I appreciate the relational quality visitors share with the sculpture, we’re running into the trouble of visitors stepping into the sculpture for photo ops.

Currently, I am drafting some language to go into a label, placed at the floor to bring more attention to the line of tape creating a boundary for the work. I would appreciate any feedback from fellow writers/museum enthusiasts!

Here is what I have so far:

Please take all selfies on this side of the line

Please take all selfies a safe distance from the artwork

Looking photogenic? We think so too. But keep your distance. The line on the floor will do.

Mind the humans: Please take your selfies on this side of the line

We just need a little space to settle this. Please stay behind the line.

Acknowledging the Selfie seems to be an informal and relational interaction with the visitor, so I am tempted to use a more informal tone. Does your museum have a similar sign? How do you negotiate selfies with your visitors?

To be fair, staying on the proper side of the line still lends itself to a nice selfie composition:

The visitor experience:

my existential crisis in 144 characters

museums are f***ing awesome: my experience with Museum Hack

Wait…what?

No, I don’t think that museums are boring.

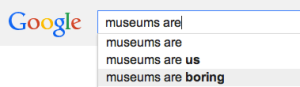

I am an incredibly biased museum worker who thinks that museums are awesome spaces for encountering objects, exploring new ideas and socializing with friends and family. However, it’s hard to ignore the stigma that comes with museums when MUSEUMS ARE gets finished with BORING in the google search box.

We live in exciting times on the museum frontier. Museums are rethinking how they connect with audiences. Transparency and accountability are becoming standard values and ethics in practice. This is a space to explore exciting ideas in museum practice, a place for me to reflect and document my own projects, and hopefully, a space to generate conversation around museum, creative and community practice.

Let’s get started.